By James Temple

On a Saturday morning in December of 2020, the RRS Discovery floated in calm waters just east of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, the massive undersea mountain range that runs from the Arctic nearly to the Antarctic.

The team onboard the research vessel, mostly from the UK’s National Oceanography Centre, used an acoustic signaling system to trigger the release of a cable more than three miles long from its 4,000-pound anchor on the seabed.

The expedition’s chief scientist, Ben Moat, and others walked up to the bridge to spot the first floats as they popped up. The technicians on deck, clad in hard hats and clipped into harnesses, reeled the cable in. They halted the winch every few minutes to disconnect the floats as well as sensors that measure salinity and temperature at various depths, data used to calculate the pressure, current speed, and volume of water flowing past.

The scientists and technicians are part of an international research collaboration, known as RAPID, that’s collecting readings from hundreds of sensors at more than a dozen moorings dotting the Atlantic roughly along 26.5° North, the line of latitude that runs from the western Sahara to southern Florida.

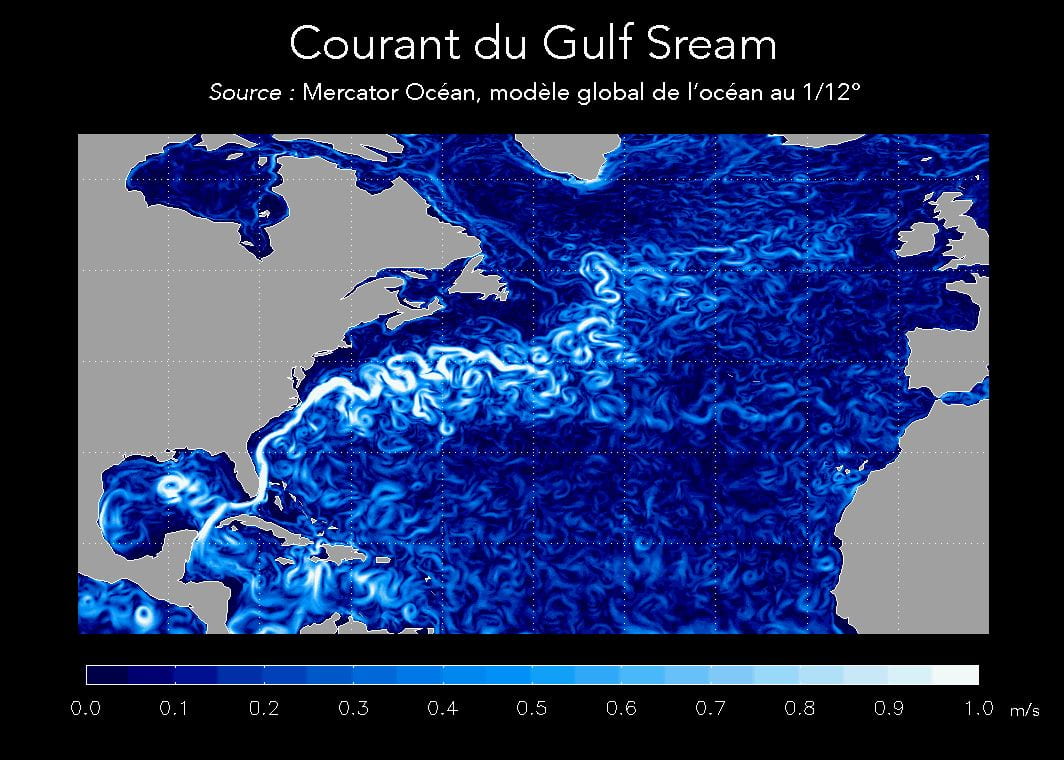

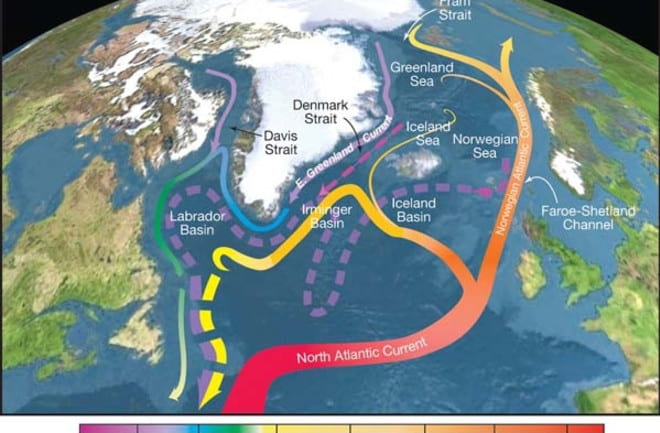

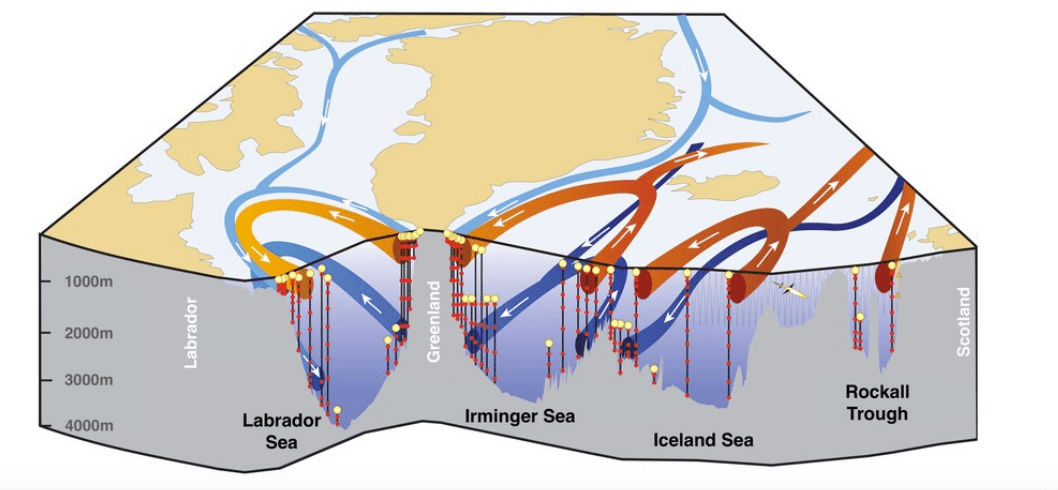

They are searching for clues about one of the most important forces in the planet’s climate system: a network of ocean currents known as the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC). Critically, they want to better understand how global warming is changing it, and how much more it could shift in the coming decades—even whether it could collapse.

Read full article: https://www.technologyreview.com/2021/12/14/1041321/climate-change-ocean-atlantic-circulation/